As I sit with a group of journalists surrounding Alice Rohrwacher, on an open terrace in Cannes, there is a dog howling and barking, far in the background. I giggle to myself as I seem to be the only person noticing it and because in her film ‘Lazzaro Felice’ (‘Happy as Lazzaro’) she features a wolf who is quite central to the story. This sound in the distance brings a whole otherworldly, almost magical element to our chat and if she does anything with her films, Rohrwacher proves a purveyor of magic through the lens.

This week, Rohrwacher descends on Doha to become a Master during their annual Qumra event. The Doha Film Institute is also about magic, and they make theirs happen behind the scenes by bringing together the crème de la crème of international filmmakers, producers, film curators, programmers, sales agent and festival directors to create a cinematic tsunami that is bound to be felt around the world. It is five days and nights of jam packed cinematic networking as well as constant learning, through their Masterclasses, lectures and mentorship, as well as over fine local dishes at working breakfasts, lunches and dinners.

From where I stand, the partnership seemed inevitable between Rohrwacher and the DFI.

Her third feature, ‘Lazzaro Felice’ feels almost like a fairy tale. In it there are elements that only by wholeheartedly believing, the audience can accept and the film needs to be viewed with an extra pair of dream glasses — as well as a belief in the idea that humanity can be good and we can find that inner good by going back to our most fundamental roots. In turn, Rohrwacher is the perfect embodiment of her name, “Alice”, except her wonderland lies within the scope of great cinema and the perfect cinematic background that our shared country of birth has provided.

As a last bit of personal info before leaving you with her fascinating interview, while I transcribed her I got goosebumps. Rohrwacher speaks in shades of deliciously true abstraction and her kind tone gets especially tender when she mentions finding her leading man, Adriano Tardiolo. It turns out this was a case of casting in reverse, because it wasn’t enough for Rohrwacher and her team to choose Tardiolo wholeheartedly after just one look, he needed to find the work within the job of the actor to choose them back. Thankfully he did. And the rest, as they say, is history.

You can watch ‘Happy as Lazzaro’ in the US on Netflix.

Do you feel there is a new movement of Italian filmmakers who are making cinema much more exiting and much more fun to watch?

Alice Rohrwacher: It’s quite difficult for me to say, from the inside considering that I’m part of it. But what I can say is that there is more collaboration. It’s true that Rome is probably no longer the center of filmmaking but we do exchange quite a lot and help each other and collaborate amongst colleagues. In the past in Italy there was a trend to name the “Best Italian Director” now it’s no longer a measure of saying who is best, but of preserving this wide ranger of auteurs, this biodiversity.

There is a sense of community then?

Rohrwacher: I’m not sure if there is yet, but I think you are beginning to feel it more.

You’ve been compared to a number of great Italian directors, from Federico Fellini to Ermanno Olmi. Who was the inspiration for you in this particular movie and in general?

Rohrwacher: I hope none of the people you mentioned are offended wherever they are. I don’t think there is a direct inspiration, rather a wide admiration on my part. The constellations of the maestros of great filmmakers, I can’t even name them, because in naming them I would set a hierarchy that is not present in my heart. They are all part of me, and the cinema I believe in and I try to make is the kind of cinema that is able to contribute to the production of a collective memory. And my memory is made up of them, of their films, therefore they are present at a very unconscious level. They haven’t passed through my head, rather my subconscious… If you perceive glimpses of them it is because they were able to produce that memory essential in a filmmaker. But then when you work with 54 non-professional actors, with children, with animals, with a wolf, with a huge crew and machines you really have no time to say “I would like to make that shot the way that so and so would have done it.” You are trying to confine this overwhelming reality that you’re dealing with in filmmaking.

The choices of names, biblical in the case of Lazzaro and also Tancredi who is named after a knight, what was the reasoning behind it, if any?

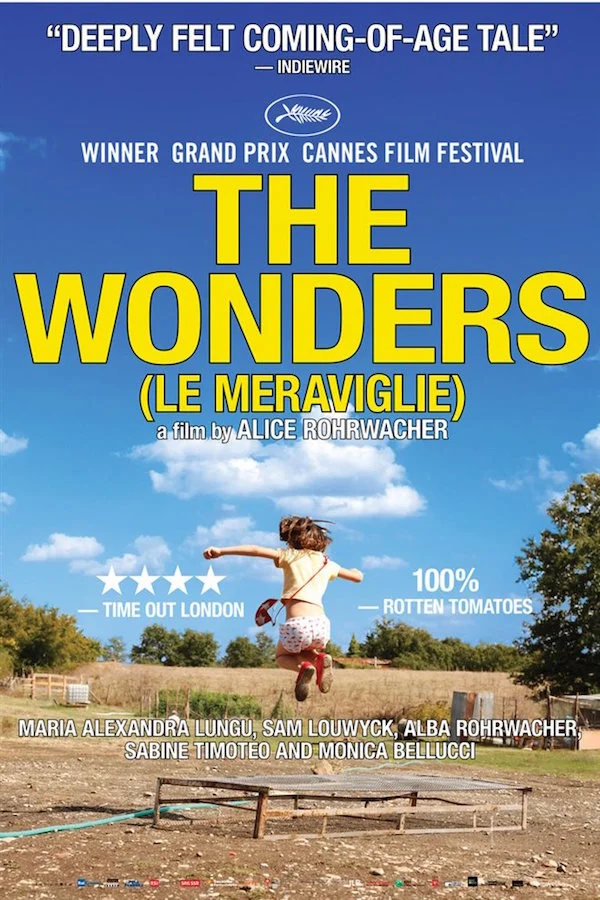

Rohrwacher: I come from a mythological country where this is everyone’s identity. In Italy we are living in a mixture of, a conflict between mythology and reality. It’s a country where small ordinary facts take on the look of legends somehow and quite the opposite, misadventures can become fairy tales. For the names, what is important for me is to draw on literary references and I did that in ‘The Wonders’ as well. In the names I give my characters I always look for a talisman, a lucky charm. I’m thinking of Gelsomina in ‘The Wonders’ and Lazzaro here. And I think that each name echoes the world it belongs to, a background and is important.

When we choose a name for a child we do the same. We wouldn’t call him or her by the name of someone whom we don’t like. It’s the same thing.

When we talk about the masters of Italian cinema we typically mention the names of fiction filmmakers. But Italy has a strong tradition in documentary. Your films are very realistic films and I would almost dare to say on the verge of documentaries. Can you talk about that, do you consciously use documentaries as a language to shoot?

Rohrwacher: It was my dream to make documentaries but I’m too shy! I started out making documentaries but there was too much conflict in myself, I would never have been able to film people in real life and crucify them, almost, in their real lives.

I thought the best way for me to make films was to give someone the gift of pretending to live in another life. For instance, in the case of this film, these are the real peasants and farmers of Inviolata. Of course nowadays they live in small families of one or two children, with their single tractor and fields, they are no longer part of the rural community that you see in the film. So they are acting out something else in the film, still remaining farmers as they are. Still I would never steal an image from anyone. We ask permission for all the images that we took and each shot is prepared and rehearsed despite the fact that it might look improvised. That’s my way of being as a human being, before being a director. It’s like a big fiction, based on a reality network and that reality is based on the fact that, just to make an example, we planted the tobacco you see in those huge plantations. We brought the animals in, and fed them, as the plants needed to be watered. There is a documentary posture, or approach in the crew, and not in the film itself.

You can feel a religious background in all three of your films, even your first short.

Rohrwacher: And I never went to a church once! They should make me a monument.

So what is your personal relationship with religion? Or is it that just being Italian you find yourself influenced by it?

Rohrwacher: I don’t come from a religious family and wasn’t even baptized, and before ‘Corpo Celeste’ I’d never been to church. But I come from a Catholic country and in some way, I’m profoundly religious.

My religion is a prehistoric religion, one that came before all other religion and all the things we’ve already told each other. Before the religion of beautiful costumes, of traditions and the religion of war, and of abuses. The kind of religion made up of human beings. My first feature ‘Corpo Celeste’ was born out of a desire to see, so I entered the Church and in particular catechism and I was really curious to see how they teach religion. How do you teach it? I went to a catechism class to observe. In this film there are plenty of Catholic references but simply because the people of Inviolata are Catholics. Religion is one of the tools that the Marchesa uses to keep people in ignorance. Therefore religion on one side is a partner in crime for the Marchesa but on the other it has a simpler dimension and is a sacred tale in a way. That’s what we hear in Antonia’s tale about San Francis.

A still from ‘Corpo Celeste’

How difficult was it for you to cast Lazzaro?

Rohrwacher: I thought you would ask “how difficult it was to cast the wolf?” Because that was the most difficult. We found him in France. It’s a French wolf.

It was challenging to find Lazzaro because we didn’t know how to imagine him. I must confess that I didn’t imagine him to be so handsome. I knew his inner quality, this light that he needed to possess, but it wasn’t something easy to cast. But that’s difficult to describe, I mean how do you say “lets hold a casting call for shining people”?! So we started out looking for a 16 to 20 year old boy. It was important for him to be young. After a while, we realized that Lazzaro would never go to an audition, because he’s Lazzaro and if he had that quality, he would never go to a casting call. At that point, we, the casting director and I, felt very miserable because we knew we couldn’t really walk the streets and ask people to be in the film, that’s only done in the movies, but we ended up going to the schools. We would knock on the doors of the classrooms and peek in, we would say “hello” and look around, to see if we could find him. Chiara one day had a look and saw Adriano [Tardiolo], and there was something in his attitude that convinced her it was him.

The problem was that when we asked him to be in our film, he politely said “no, thanks.” He admitted “I don’t know if I could ever do it, because I don’t know what kind of job it is.”

That’s when a terrible period started for me, because I was the one being auditioned and tested by him. We rehearsed the whole film, from beginning to end, with him, so he could understand what we were looking for. For more than a month we worked with Adriano hoping, but without the certainty that he would accept. At the end, I passed the audition. He cast me.

Adriano Tardiolo with Rohrwacher at the Festival de Cannes, where ‘Lazzaro Felice’ won Best Screenplay

But that was a very important lesson because our job is often overestimated. We think that whenever we ask someone “would you like to be in a film” they’ll immediately jump at the opportunity and say “yes!” But this really humbled me because it was the proof that we don’t have the power that we believe we hold because we are in filmmaking. It was a great reality check and placed me in the right position to make the film.

Can you talk a bit about the visual approach, the decision to use 16 mm, which heightens both the magical and the realism in the film?

Rohrwacher: I’ll admit I’m a faithful person. If someone is true to me, I never forsake them. And film has never let me down. It never disappointed me or created any problems for me, so I have no reason to move to digital. I think it’s a very powerful, beautiful, concrete and reliable technology. It works wonderfully because it’s very mechanic and concrete in the sense that at the end of the day you have your reels, your dailies that you have to go through and it’s a living technology.

I strongly believe in the image because it is able to combine many things which in our daily life are separated. Life separates and the image unites. An image holds everything together in a shape that you cannot control. It has its own life and it’s independent. It has its say in filmmaking.

It’s really a threesome — we the filmmakers, the actors and it.