Back in 2012, I met Nanni Moretti in his office, and the meeting changed my life. Forever. Moretti has that power, to change the course of things with his cinema. I’d watched ‘We Have a Pope’ in Abu Dhabi and not long after, I decided I needed to meet him face to face. In person, he was what he is in the movies. Nothing more, nothing less. Cranky, at times mean, and then, once I’d slammed my fist onto his desk because he wasn’t paying attention to my questions, he became a talkative, kind and attentive interview.

I love his cinema. He, I hate and love, depending on the day. But these days his films are getting the attention they deserve at Film at Lincoln Center, with ‘Caro Diario’ opening on May 15th, via streaming and ‘Santiago, Italia’ still on their playlist. Watch them. They will change your life too. Guaranteed. But here I revisit part one of our 2012 interview. Stay tuned for part two….

Originally published on HuffPost in March of 2012

These days, Nanni Moretti seems to be everywhere. Featured in the Italian media talking about the Taviani brothers’ Berlinale winner Caesar Must Die, in NYC this month for a retrospective of his work at the IFC Center and the US release of his latest film We Have a Pope (Habemus Papam), in London next month for another retrospective and then off to Cannes in May as this year’s President of the Jury.

Cannes festival president Gilles Jacob said about him “When we decided to put Ecce Bombo into Competition, when I first arrived in 1978, it was because I had a premonition that Nanni Moretti would soon become NANNI MORETTI.”

So for this expat yearning of home to whom Moretti represents the best of contemporary Italian cinema and the alluringly inexplicable energy that is modern Rome, having the chance to interview him is a dream come true.

While waiting in the offices of Sacher Film in Rome, having arrived too early, I get a chance to revisit one of my worst nightmares: the one in which our interview turns into the infamous “words are important” scene from one of Moretti’s earlier films Palombella Rossa (Red Lob). In it, his character Michele becomes incensed by a reporter’s cluelessness and ends up slapping her for using a series of clichés and banalities.

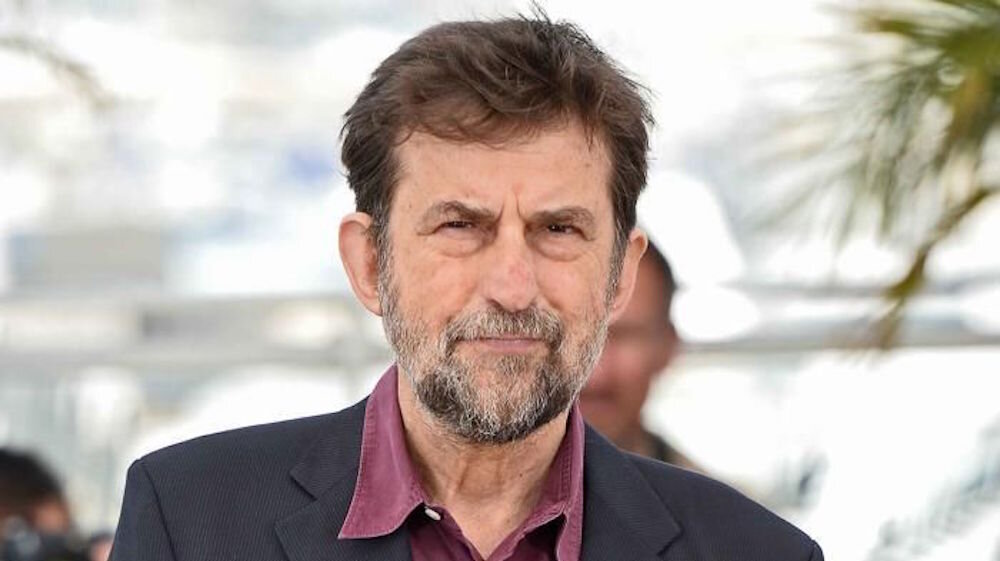

At first glance, the real life Nanni Moretti could appear quite like the men he plays in his films. He walks into the Sacher offices - named after his favorite torte - still wearing his scooter helmet (the look he made unforgettable in Caro Diario). He’s as understatedly elegant, tall and handsome as he looks in The Son’s Room (La Stanza del Figlio), Il Caimano and We Have a Pope and he’s fiercely intense in the delivery of his opinions.

Yet there is a magnetic radiance within his frown, a softness to his words, even spoken in his signature authoritative timbre, once he finally relaxes into our conversation. His sentences are full of hope, phrases like “we should always strive to do something better, I like to remain trusting and continue to believe. Also because life can bring such great surprises...” So unlike what I’ve heard from many of my countrymen in the last few days, who only see doom and gloom for Italy in these uncertain economic times. Of course, Moretti does concede that Italy currently is “a country that’s gone a bit crazy.”

At the very start of our conversation, Moretti firmly establishes “you see, this is an important thing about my work, I like to do, not explain. I love making a film but then explaining my choices afterward bothers me. The world of cinema is full of people who talk, talk, talk, complain, complain, presume, are overly ambitious, make plans, but instead, I like to produce, to do.” It’s wonderfully refreshing to be in the company of someone who tells it exactly like it is, doesn’t manipulate or create a need to speculate on what he’s feeling and thinking. And in the world of entertainment, it’s downright unequaled.

Once inside his office, a beautiful room painted in Roman red with a picture-perfect view of a tree - complete with birds chirping - outside the window, Moretti speaks candidly. “I prefer to remain naive and continue to hope, rather than become cynical” he admits, when I question whether it is possible to be spiritual and a great leader in today’s world. It’s a profound quandary he has raised with We Have a Pope, one he continues to strive to answer with Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s Caesar Must Die (Cesare Deve Morire), to which he owns the distribution rights in Italy. The film that, thanks to his vision, this past February was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlinale and has been wholeheartedly received by Italian audiences and critics alike.

When I tell him he’s changing the landscape of modern cinema by distributing films like Caesar Must Die - as well as Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation, acquired by Moretti’s Sacher Distribuzione long before its Oscar win - he dismisses it as “luck, it’s very simple, I was lucky”. While playing with a Rubik’s cube on his desk, he continues “all the other Italian distributors who saw the Taviani’s film before me - strangely, I was the last one to watch it - had found it ‘beautiful but unsellable’ or ‘beautiful but difficult for an audience’. I could agree with them, but personally, I stop at the first word: Beautiful. Therefore, if I have a distribution company, it’s my duty to distribute it.” I prod him further which allows for yet another glimpse into his realistic style of optimism “lets just say that I believe an audience for these films exists.”

And so I begin to unravel the fascinating philosopher behind the filmmaker, the man who through his intimate films reveals an infectious love for world music, his passion for playing water polo, an admiration for people who really know how to dance, and is the doting father who, for a while, bought Mickey Mouse figurines for his son Pietro, then admitted to the merchant that the collection had long ended up being for himself.

Moretti is incredibly busy these days, between promoting Caesar Must Die - currently playing in cinemas throughout Italy - an upcoming trip to NYC and his pending duties at Cannes. Yet when I suggest that I can take his leave, after half an hour of engrossing conversation, he assures me that, his next appointment already waiting for him, we can still continue a while longer.

Even as a distributor of Iranian movies and independent world cinema in Italy, Moretti claims “I am not an expert” but because he owns a movie theater, the Nuovo Sacher near Porta Portese, “I showcase films that I would like to watch at the movies, even if I believe they are not popular, or a bit difficult, but because they can generate an audience.”

Moretti vehemently denies that his medium can change the world because he thinks “when a filmmaker decides to change the world, most likely he will end up making movies that are mediocre, patchy and raw.” He adds “changing the world takes centuries and isn’t done through films, but it would be a great personal achievement to change the cinematic market a bit.”

“Unfortunately, in Italy we don’t have what the French have, an atmosphere around the movies that at once fuels artistic expression as well as the industrial aspect. In France, cinema is considered a national treasure. In Italy, it’s all very casual, there is only one TV program devoted to discussing films and so all promotion is left up to individual producers.”

I point out that independent cinema has its challenges in the US as well, like getting an audience and making it through the first box office weekend. Moretti shares “in 2007 and 2008 I was the director of the Torino Film Festival, a distinctly beautiful festival, where I had the chance to watch great US films that were never released there, most digital, going straight to DVD or shown on cable.” He continues “see, I am not familiar with the American market, but there it would be fundamental to create a circuit of thirty, forty cities, find agreement between distribution companies and showcase different films, films that don’t conform to the standard, around the US.”

He no longer reads any reviews of his films which he consistently saved in his “younger days” and prefers to be in touch with his audience instead.

“It would be wonderful if instead of so many opinions, people had more principles” he points out, and has grown “accustomed but never resigned” to people who haven’t watched his films and unavoidably judge them.

While I do hold my own magnificently steadfast opinion of Nanni Moretti, I am curious to know how he views himself. The words he chooses, after complaining three seem at once “too few and too many” are “volatile, a perfectionist in my work and also... a little obsessive. Oh, and touchy, but I’m not conceited.” He confirms that he holds “a very different opinion of myself from what others believe. I know almost all Italian filmmaker, young, old, good, bad, likable, unpleasant, thin, fat, tall and short...” He smiles, distractedly fixes a button on his shirt collar, then adds “and I’m definitely not on the higher half of their average median of self-importance. Easily offended, yes, but conceited no, no more than average.”

But perhaps the most powerful message I take away from my time with Moretti is what he says about being able to spend time alone, a commendable quality which he nearly dismisses “it may sound like a banality, but I know how to be alone, because someone who can’t spend time alone, doesn’t enjoy it, well, he can’t really enjoy himself around other people.”

“La Vita è Cinema: The Films of Nanni Moretti” will run from March 28th through April 5th at the IFC Center in NYC. The retrospective includes twelve of his films, among them I Am Self Sufficient (Io Sono un Autarchico), The Caiman (Il Caimano), Caro Diario, Aprile and The Son’s Room, as well as one of Moretti’s favorite Abbas Kiarostami film Close Up.

Top image courtesy of Sacher Film, used with permission