From Walter Salles it was about the power of kindness, from Darius Khondji it turned out to be about our individual learning pace and from Anna Terrazas, a lesson in adaptability… Among others. Read on for all the important lessons I learned at this year’s annual DFI industry incubator.

Ask yourself, how often does someone teach you something important about life? For me, it’s an everyday event, as people often enlighten me about kindness, or the lack thereof, in their simplest interactions with me.

When it comes to cinema, I don’t learn lessons as often, although films do give us a message of course we take away often without knowing it. But at times I’ll watch a TV series or read a book, so film, a whole film projected on the big screen is not a part of every minute of my everyday life.

While in Qatar last week for the Doha Film Institute’s annual industry incubator Qumra, I did learn something cinematic every day, from the Masters in conversation there with the brilliant Richard Peña. A diverse group hailing from all corners of the globe and practicing a few different disciplines, I found their lessons invaluable and so I am sharing them with you.

Walter Salles — kindness as a superpower

Kindness is intrinsic to Oscar winning Brazilian filmmaker Walter Salles. Having already interviewed him before he conquered the golden statuette, in Marrakech, for Flaunt, I wanted to see if success had changed him. Turns out, it did, for the better. I mean, just when you thought he couldn’t be more giving, he surprised me by opening his masterclass by thanking “a filmmaker I adore so much, Elia Suleiman,” for having invited him to Doha. Classy. And he indulged everyone’s cheeky request for a selfie during his meetup with the press the following day. And smiled during them too.

He also proved very generous when he credited Gael Garcia Bernal, as well as Fernanda Torres who won a Golden Globe for her role in Salles’ latest I’m Still Here — as a “co-author.”

Listening to Salles speak about filming Central Station with Torres’ mom, in real life, Fernanda Montenegro while she remained mostly unrecognized among the non-actors reading out their letters, made me want to rewatch his poetic masterpiece. And watching a scene from The Motorcycle Diaries, the one where Garcia Bernal and Rodrigo de la Serna — playing Che Guevara and Alberto Granado respectively — pick up two sisters so they can get a drink and perhaps even score some food, made me yearn for that time I first watched the film and it made me dream. Of distant lands, faraway times and legendary figures who are no longer among us.

Salles credits iconic humanist photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, as well as Italian Neorealism, the French Nouvelle Vague, but also Michelangelo Antonioni — he mentioned in particular his 1975 film The Passenger, starring Jack Nicholson as one that posed him questions on the loss of identity. He also predicted that Brazilian cinema would wow us in Cannes this year — Brazil is the country of honour in the Cannes Marché du film — and of course, proved prophetic as The Secret Agent (O Agente Secreto), directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho was announced in the main Competition by festival head Thierry Fremaux, the day after the end of this year’s Qumra.

Darius Khondji — learning at one’s own pace, in one’s own way

The French-Iranian cinematographer, who has worked with Bong Joon-ho, David Fincher, Woody Allen, Wong Kar-Wai, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, and James Gray among others, cited Egyptian films, Arabic cinema and Italian Neorealism as his influences while growing up. He studied filmmaking at NYU and pointed out that he found living in NYC at the time, in the 1970’s, the most important thing for his art. Khondji admitted to learning technique “by testing things, not by reading books” because, he admitted out, “I’m not a technical person.”

Darius Khondji, photo courtesy of the DFI, used with permission

The first clip Richard Peña showed of Khondji’s work was for Madonna’s Frozen video, directed by Chris Cunningham. The DoP of the stunning blue and black video, where the superstar wears looks from Jean Paul Gaultier’s SS1998 ready to wear collection, talked about the director’s precise vision and admitted that “Madonna and I were doing what he wanted.”

For David Fincher’s Seven, Khondji hid silver, gold and white cards around the set to add light to a pitch black scene, where no artificial light was used, and the actors — Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman — shined their flashlights on the cardboard cutouts to create the light of the scene. That was a fascinating moment for me, as I learned a kind of trick of the trade, which I would never have thought about on my own. How often when we wear a certain color, it does something for our complexion, makes us shine, right? I also, for a moment, remembered someone who said to me recently about never being able to wear white after 50. Which of course is pure BS as I wear it often and proudly and that ship has sailed. Just watch this video for an example… Yup, that’s me wearing a white shirt studded with rhinestones, a charity shop find.

What I loved hearing and my takeaway from the masterclass was Khondji’s sense to freedom when it comes to his art. He learned what he wanted to learn, at his own pace and without giving into outside pressures, to become one of the greatest cinematographers who has ever lived.

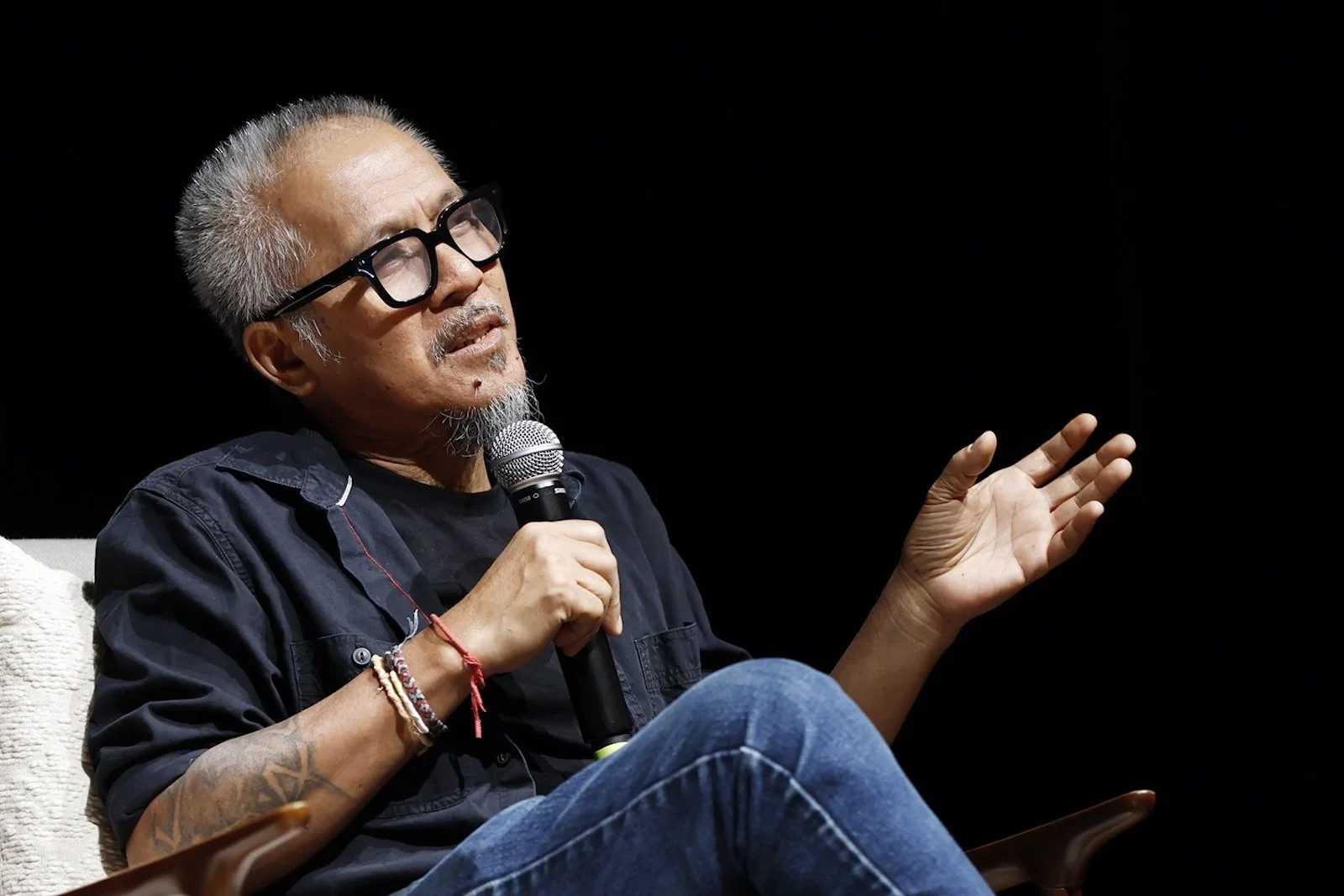

Lav Diaz — cinema as life nourishment, not just a candy

Filipino, or better yet Malay filmmaker Lav Diaz sprinkled his masterclass with descriptive expletives. It is the way Diaz is, a bigger than life personality wrapped in a lithe body, his ever-famous ponytailed long hair now cropped into a silver buzzcut which only highlights his rockstar vibes. During the masterclass, Diaz admitted it was either “rock and roll or cinema — but rock and roll is poverty and drugs,” so he became a filmmaker instead. Diaz didn’t spare words when it came to world leaders and his lessons on cinema and the world were as plentiful as his swear words.

Lav Diaz, photo courtesy of the DFI, used with permission

The biggest lesson I walked away with from Diaz has to do with the way we should watch cinema. His cinema, of course, where a film at times can last as long as 9 hours and where his shortest work, a special cut only to be lengthened at release, is timed at 2.45 hours. When I sat down with Diaz after his masterclass, for a short interview which will be included in a Qumra podcast I’m working on, the Malay filmmaker talked about cinema in terms of food. “It’s not a candy,” he said, meant to be savored once in a while, but actually food. Cinema is nourishment and it should be around us all the time, even if that means walking in and out a film — as one is forced to do with Diaz’s longer works — going for a walk, having a break and “having sex with your girlfriend,” as he confirmed during his masterclass. This idea that we can live with film the way a lot of us live with music, as a soundtrack of our lives, is at once liberating and also invigorating. I would not mind owning all of Diaz’s work and playing them back to back on my TV, as a sort of black and white leitmotif to my life. Wow. That statement turned out to be groundbreaking for me. Simply enormous.

Another lightbulb moment was when Diaz talked about his latest film Magellan, which stars Gael Garcia Bernal and is a historical epic based on the last two years before Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan set off for his famous expedition. Diaz hoped the film would be unveiled in Cannes, and actually wasn’t announced in the first round of selections last week, which provides yet another lesson, this one about how a seasoned, respected filmmaker whose work is on every film lover’s radar can still be initially “ignored” by a film festival, giving hope to all those first and second time filmmakers I mentored at Qumra in the art of media etiquette. Yes, Diaz too has to bow to the gods of Cannes, still.

But the main lesson, which got away from me in the paragraph above, actually had to do with Magellan’s death, the real man and how his life ended. If we know history, we also know that at age 41, Magellan was killed in what is now the Philippines, first speared and then finished off by other weapons, held by men of course. And Diaz admitted “the nature of my people, the Filipinos are very violent, as Magellan found out.” Now, to anyone who has been lucky enough to speak with Diaz in person, he’s kind and gentle, soft spoken and not aggressive. And if your interactions have also included some with his fellow countrymen and women, it’s always in a peaceful tone, so his statement was a wakeup call to rewatch his work, and notice this darker thread which of course, he’s always put in plain sight but I never connected to before.

Anna Terrazas — being resourceful, and what you wear changes you, or your character

Perhaps the biggest lesson from Mexican-born, NYC educated costume designer Anna Terrazas, who has worked with brothers Carlos and Alfonso Cuarón, as well as Mexican auteur Alejandro G. Iñárritu on some of their iconic works of the Seventh Art, came in the first ten minutes of the masterclass. It had to do with adaptability and how Terrazas went door to door in the village where they were shooting the film Rudo y Cursi, exchanging brand new clothes with the ones already worn by the locals. While the film, directed by Carlos Cuarón and starring Diego Luna and Gael Garcia Bernal, takes place in a fictional farming village named Tachatlán, located in the Cihuatlán Valley of Jalisco, Mexico, the region it describes is known for its banana plantations. And anyone who lives there comes in contact with the plant and its fruit, which upon cutting releases a kind of sap, that according to Terrazas stains clothing in a particular way. Unable to reproduce it exactly the same, the costume designer and her crew went to every door, asking the occupants to give them their old t-shirts, trousers etc, in exchange for the new ones they had bought — which must have seemed an absurd request.

From left, Richard Peña and Anna Terrazas, photo courtesy of the DFI, used with permission

Yet, every time I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing a costume designer, the message from them is always about adaptability and the ability to invent something from nothing, oftentimes, to satisfy the director’s vision. It’s a wonderful lesson in life too — the fashionista equivalent of ‘when life gives you lemons…"

Famous for her work on The Deuce, the TV series created by George Pelecanos and David Simon, which takes place in NYC in the early 1970’s and focuses on the burgeoning porno industry back then — which included drug dealers, prostitutes with their colorful pimps and dubious nightclubs connected to the Mafia — the series proved the perfect stomping ground for an emerging costume designer with a rockstar sense of style. In person, Terrazas sports tiny tattoos at the corners of her eyes and was wearing diamond studded black Mary Janes with cropped loose dark jeans and a black t-shirt, accented by a red Mexican woven sash belt worn as a scarf. I mean, my eyes did not know where to look, honestly!

Terrazas also designed the costumes for Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, which presented its own costume challenges as it was shot in black and white and color is a big part of that conversation, as different shades read as different kinds of grey on film.

The tall, slim Terrazas also talked about the importance of one piece of clothing in defining a character and admitted she spent months looking for the perfect suit for Silverio (played by Daniel Giménez Cacho) for Iñárritu’s Felliniesque and very personal film Bardo. In The Deuce, she differentiated between the two twin brothers who run the nightclub, both played by James Franco, by giving the more flamboyant Frankie “Cuban heeled” boots and bartending Vincent some 70’s Chelsea boots.

And that’s an important piece of information, one I often refer to but not so consciously, in my own work. When you wear something, that piece of clothing or outfit changes you, for the better or the worse. It’s why I tend to include a short chat about what to wear to an interview when talking to the filmmakers I mentor. What you wear is your armor, and if you feel confident and bigger in it, you’ll exude that confidence to others around you. Just think of the last time you wore that itchy sweater or shoes that pinched your toes, and what your day felt like in those uncomfortable pieces. Just like what you read, watch, see, and listen to changes you, so does what you wear.

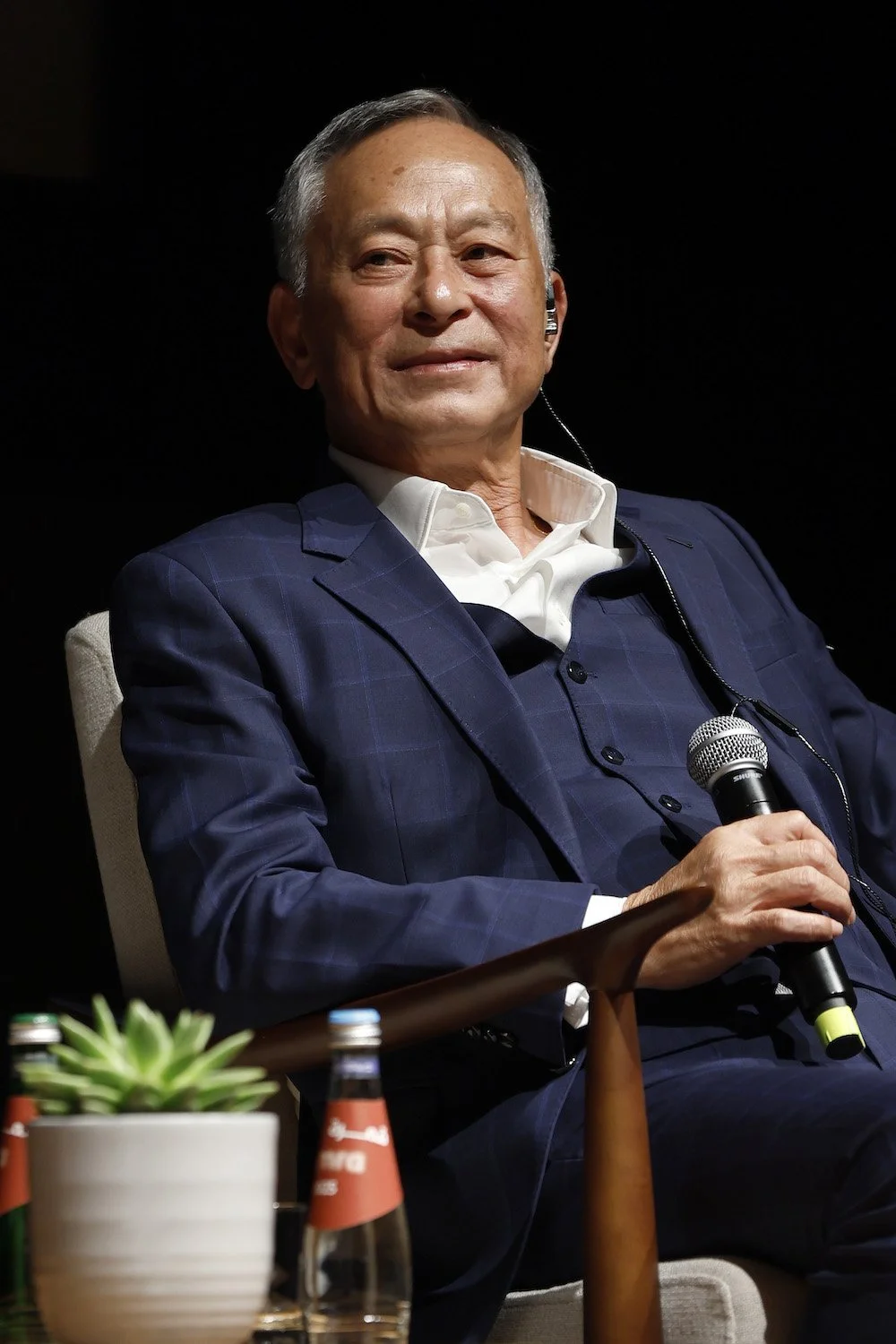

Johnnie To — adaptability is key and cinema must evolve

I have to admit that when I met Hong Kong Master filmmaker Johnnie To, I used the lesson I’d learned earlier on from Walter Salles — kindness is a superpower. I could tell To was being pulled in all directions and, surrounded by his entourage, he didn’t feel completely at ease. Dressed in a crisp, elegant camel colored cotton suit, the slim To sat down, with his Cantonese translator next to him. As I asked him about film festivals — To is a veteran of Cannes, Venice and more — he seemed to provide me with short answers that were perhaps, a bit defensive. “My films are not popular,” he said at one point. I grabbed that opportunity to turn things around and, channeling Salles’ kindness, I complimented To on his style of cinema and even asked him if Mad Detective is his “superhero” film. By the end of our short chat, he was not only speaking to me in English, foregoing the translation to communicate more directly, but also became the warm and bright man we all know him to be — through his “fun films,” as my esteemed Indian colleague Shubhra Gupta calls them.

About being in Doha, To pointed out “I see great opportunities in Doha. I wouldn’t have come here for no good reason. Different eras offer different opportunities and if you do not change, if you stay the same, it will be difficult to see something new happen.”

To, who was also mentoring talents at Qumra and took a seat in the afternoon sweltering heat outside, wearing his crisp suit, to speak to some of the projects assigned to him, also said during the Masterclass that he was impressed by a project by a Qatari director. It sets an example of “how the history of movies will evolve, and how filmmakers [anywhere in the world] can evolve into world-class directors as long as there are opportunities to keep going.” I have to agree, as I know exactly what project he was talking about — remember I saw him meet up with them while I myself was sitting outside in one of my sessions — and this woman filmmaker, from Qatar, is a powerhouse. One who will bring to the world the first feature film project from her homeland to appeal to international audiences. Mark my words.