It’s a fact that there has never been such a movement of global general uprooting, in the history of our planet. Most of us feel deep inside ourselves a sense of dissatisfaction and the easiest way to deal with it seems to be to pick up and leave -- for work, love or life experience. But that can also turn into the most difficult decision of our life, because sometimes you cannot go home again.

As an old friend used to remind me, in moments when even traveling to the other end of the planet hadn’t really fulfilled its purpose, “Nina, the problem is that when you travel, no matter where you go, you’ll always take yourself along.” It’s so true, our inner struggles transfer unfortunately well, hidden within the deep recesses of our beings. And even the furthest journey ultimately finds us as our own regrettable travel companion.

Miguel Angel Moulet’s haunting, sultry and perfectly shot film ‘Todos Somos Marineros’ (‘We Are All Sailors’) tackles that idea, but also mixes in several other themes, including the rhythm of language and how we change depending on the words we speak, as well as the filmmaker’s own unresolved childhood family mysteries.

The result is a spellbinding film that entertained but most importantly, stayed with me — to beg more questions to be asked and demand that I answer some of my own personal riddles. It’s a rare and precious thing when a film manages to do that.

The story of ‘Todos Somos Marineros’ revolves around three Russian sailors stranded in the Peruvian port of Chimbote, after their boat’s parent company goes bust. They commute between the ship and the port for their mundane daily needs and try to survive as best they can, while awaiting what to do next. But in the synopsis for the film on the International Film Festival Rotterdam website — the film world premiered at IFFR — there is a sentence that brings Moulet’s simple story into our daily lives:

“Without any heavy-handed comparisons, we can clearly make out the contours of a global diaspora: the rootless army wandering the world in search of a place to survive.” And that’s where the filmmaker’s genius truly lies.

I was thrilled to sit down with the filmmaker himself, and have a member of his talented crew Katitza Kisic generously translate, while his cinematographer Camilo Soratti sat in on the conversation. On a chilly day in Rotterdam, within this magical festival that allows contacts and connections without interference, it was a beautiful encounter, to explain a perfect film.

This is of course due to my own shortcomings but the last Peruvian film I watched was ’Octubre’ by the Vega brothers and I noticed, without thinking about it, that your film has a similar tint to theirs. What do you think makes for this unique coloring in Peruvian cinema?

Miguel Angel Moulet: It’s because of the Andes. In Lima it’s always cloudy and the sky is grey all the time. It’s even called “the belly of the donkey” (panza de burro). In Lima we say our sky is like a donkey’s belly. And the Vega brothers are making a film with four other filmmakers which is incidentally called ‘Panza de burro’.

What made you choose this particular subject for your film and these Russian sailors stuck in the port of Chimbote?

Moulet: I wanted the Russians because their language is so different from the Spanish. It’s also a thing for me because it addresses detachment, becoming separated from your country — like you are no longer there.

Personally, as an Italian who grew up in the US, language is important. My birth language possesses a certain power that my adoptive language English does not. It’s a different rhythm.

Moulet: Totally. In my own life, I won a scholarship in Canada and went there without speaking either English or French. I started to learn a little bit while there but I was for six month without knowing anyone, and it was a cold winter, minus 30 degrees at times. I was writing the script there so it was an experience for me also.

While I was there I had a friend from Cuba, a sound man, and we talked a lot about the sound. And this man had a Belgian girlfriend and she told us she was so happy to speak with us in Spanish because she felt like it was a more affectionate language and that when she was in Belgium she felt more reserved, because of the language. I thought about that also for my script.

Even your Russian characters become more affectionate, warmer when they speak Spanish!

Moulet: That’s why the role of Tito is like a bridge in the film. He travels between the two worlds, from the boat to the docks, from the Russians to the Peruvians. There is a scene in the movie when they are walking in the market and start comparing languages, and naming words in each language. And it was important for me to connect the characters with their languages.

Without giving the ending away which can actually be interpreted in many different ways by audiences, do you think for you personally there is a certain liberation in being the outsider somewhere?

Moulet: I don’t know. It’s an open finale. I think everyone can have a personal resolution for the film.

But you personally created this work while being an “outsider” of sorts in Canada. Do you think that being one, as a man, gives you a certain freedom?

Moulet: I’ve been in Cuba, in Canada, in Japan, but I don’t feel I’m on the outside. I’ve talked with a lot of people about uprooting which is not an emotion but a state of mind. I mean, it’s a feeling but not an emotion, which is more fleeting. I like to work with that because it gives me another kind of freedom.

My grandfather, I never had a chance to meet him, arrived in Peru from France. He met my grandmother there. But I don’t know what happened, he must have done something bad because these days no one talks about him. I don’t have a lot of information about him or what happened. I also used that idea for my story.

While in Canada, one day I went to buy cereal, braved the cold and entered a supermarket, and when I paid, the cashier talked to me in Spanish. It was such an impactful moment that I went back inside the store and bought something else, just to talk to her some more. But it was a little sad, because I asked her if she wanted to have a coffee together, to talk and she thought about it but answered that she had a boyfriend.

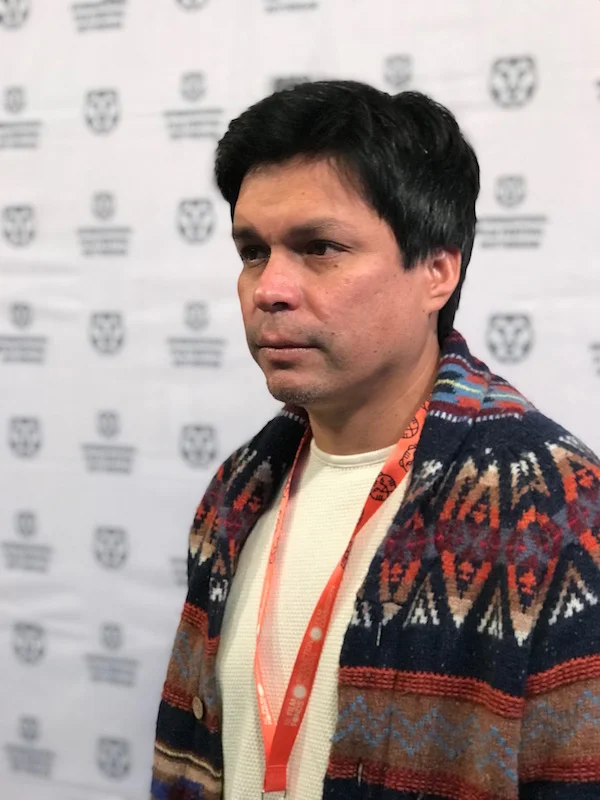

Filmmaker Miguel Angel Moulet at IFFR

But you just wanted to hear the sound of your language, it wasn’t a romantic proposal!

Moulet: No, exactly and I also wanted to say to her, I have a girlfriend too! But I didn’t say that, and I imagined that’s how my grandfather met my grandmother. I also didn’t want to analyze it all too much.

While I was thinking of writing the movie, I had also seen a report on the news about three sailors on a stranded boat and a journalist who went to the boat to interview them. And I got to thinking about it, how these men only got off the boat to go to the market, to wash their clothes. How they needed to do basic, everyday things, in this extreme situation.

They didn’t have electricity on the boat. And the journalist asked them if they wanted to go back to their country, if she could help them and they said “it’s OK, if you want to help us it’s OK, but we’re OK here also.” And I stayed with that idea that they were OK going back, but also staying there.

That’s a whole other interview right there! Your producer was talking about her experience here, so I wanted to know your experience in IFFR. What did you learn from the audience and the festival?

Moulet: I’ve come with my wife and my little one-year old daughter, and my wife was also involved in the movie along with many with whom I studied in Cuba — including Camilo, my DoP. It’s a movie that is from all the people who were involved in it.

It’s a community more than a movie!

Moulet: For me it’s really special to come here to share it with them, to get a chance to meet here and watch it on a giant screen — it’s a beautiful experience.

Also I’m working on my next film featuring a Japanese migrant and we’re looking for a co-production with Japan. It’s going to be filmed half in Japan and half in Peru. In Peru it seemed all so far away but after attending here it has become more possible.

It’s a story about uprooting as well. I have a brother who moved to Japan for two year, to work in a factory and ended up being there for fifteen years. So the film goes into what I think happened in Japan, since when he got back I was a grown man and we didn’t get to speak about his experiences together.

IFFR a very important festival, and also the boat that we filmed on was a Dutch boat. So it’s an interesting coincidence. I guess we’ll have to look for a Japanese boat now…