In typical James Ivory style, which we have come to know and love in the beautiful films he has been a part of throughout his career, much of the story of this moving documentary is written between the lines.

For someone like me, who grew up watching and rewatching all the Merchant Ivory Productions masterpieces, A Cooler Climate is a special gift. The kind of gift that if we still lived in an era when DVDs were available, and could be played on the now obsolete player, this would be one disk bought with excitement and then kept on the easily accessible middle shelf of our collection, to be watched every time one's soul needed healing from our big, bad world.

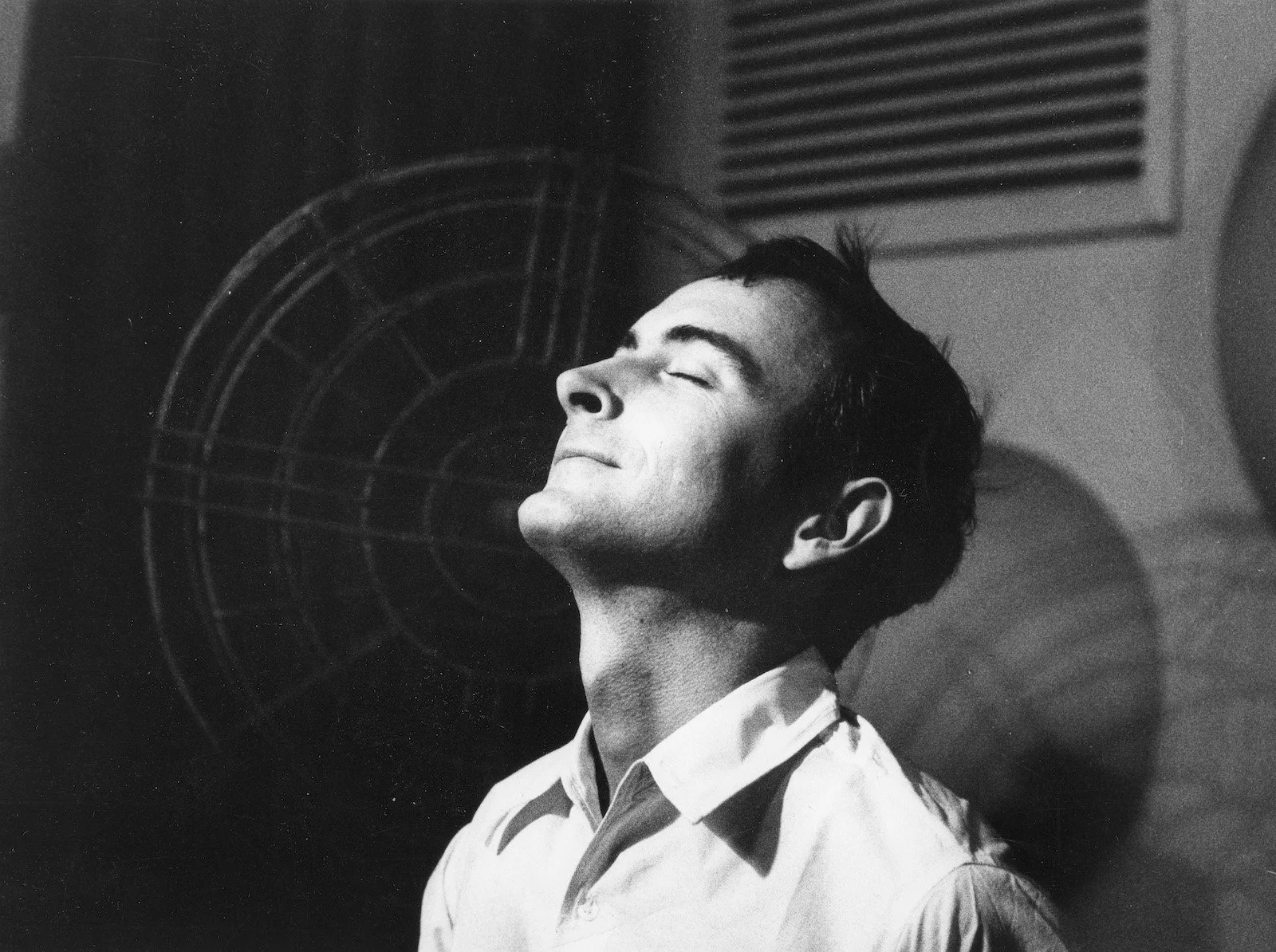

In 1960, filmmaker James Ivory was still finding his cinema legs, before going on to become the director of such hits as A Room with a View and Howard's End, not to mention the Oscar-winning screenwriter of Luca Guadagnino's Call Me By Your Name. And in search of architectural wonders in south Asia, he took on an assignment to shoot some footage in Afghanistan, with the intention of making a documentary about the country. He chose Kabul to escape the Indian heat, he admits in his soulful voiceover for A Cooler Climate, which half discloses the meaning behind the film's title -- with one more definition to come. Afghanistan then was a different place from what it is today, and yet blue chadors can be seen worn on the streets in Ivory's footage, though he explains were not imposed upon women as in today's Taliban-controlled Kabul. Ivory, a young man who grew up in Oregon, within a well to do family (his father owned a lumber yard that supplied Hollywood studios) found the journey liberating and we immediately understand why.

Away from the America of his parents, and his very heterosexual looking classmates, the sensitive Ivory found a world with a fluid sense of sexuality, which is something immediately apparent when one visits that side of Asia, even today. Men holding hands, girls dressing as boys to be able to work, it's all something that can be seen in that part of the world. In a wonderful parallel, and a brilliant plot ploy for the film, excerpts from the Bāburnāma, which are the memoirs of Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn Muhammad Bābur, are interspersed into the film, giving A Cooler Climate context in terms of place and cultural norms. Granted that the great Emperor Babur, who crossed over into India and became the founder of the Mughal Empire there, lived in the 15th and 16th centuries. And yet the words from his memoirs, read in voiceover throughout the documentary, feel at once contemporary and actual. It seems that his Afghanistan and the one Ivory discovered five centuries later are one and the same and Babur's candid insight into his own fluid sexuality seem to mirror the protagonist's journey.

But here is the alternate meaning of the film's title. In the last fifty years, our world has changed, it has foregone the cooler in favor of the hot and bothered. Our fellow humans destroy and cancel, everything and everyone who doesn't agree with their viewpoint. It is like a world where the Taliban is among us, everywhere, on social media and in casual conversations -- we criticize the Afghani type of intolerance but are getting more and more used to the Western, garden variety, everyday kind of fanaticism.

I found myself crying often, big hot tears while watching the documentary, co-directed and co-written by Ivory with Giles Gardner. Why cry, you may wonder? Because not only the Afghanistan portrayed in the film is gone, but so is the kind of world that celebrated the films made by Ismael Merchant, James Ivory and their constant collaborator, writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. If you doubt my words, all you need to do is look up the reviews for this documentary, which are too few and far apart for such a masterpiece of filmmaking, and use words like "sprightly" and "high-burnish" when describing the magnificent score by Alexandre Desplat, which accompanies the viewer throughout the film with class and care.

At one point, the faceless Buddhas of Bamiyan are shown, still standing of course in their full majestic beauty. It proves a blood curdling moment, as one realizes through Ivory's ever brilliant commentary that these magnificent statues withstood the test of time since the 6th Century, only to find their destructions at the hands of men -- Taliban men who considered their different religious provenance offensive to their own insecure sense of spirituality.

The film uses Ivory's 16mm vintage footage, his family's extensive archives of mementoes and photographs which have all been carefully preserved, Ivory's delicious narrative voiceovers and the Bāburnāma to tell a story that feels so completely cinematic I was sad when it came to an end. Gardner, a longtime collaborator of the filmmaker and a film editor, puts his perfect credentials to use and helps construct a quick paced yet very smooth film, one that beckons the viewer to return to it, again and again, like a familiar Rumi poem. Or a personal mantra, something which makes each day more pleasant and reminds us of how lucky we are to have culture and cinema in our lives.

In a particularly poignant moment in the film, one that points to our common destiny as something already measured and decided by the powers that be, Ivory talks about his chance meeting with Ismael Merchant, who became his partner both in life and in the movies. But in typical James Ivory style, which we have come to know and love in the beautiful films he has been a part of throughout his career, much of the story is written between the lines. As if small snippets of subliminal images were edited into the documentary, we find hidden meanings and secret passages in much that isn't said, but can be seen if only we know where to look. And how to listen.

United Kingdom, 72 minutes, 2022

Dir: James Ivory

Co-dir: Giles Gardner

Writ: James Ivory, Giles Gardner

Prod: Bertrand Faivre

Cinematography: James Ivory, Giles Gardner

Editor: Giles Gardner

Sound editor: Carole Verner

Music: Alexandre Desplat

With the voices of: James Ivory, Umar Aftab and Giles Gardner

Images courtesy of The Bureau, used with permission