When the US wanted to use art to conquer the world, they enlisted the help of an up-and-coming American artist, a Jewish Italian art dealer and a woman with political connections. The result was a victory like no other, the story told in a wondrous documentary which is releasing this weekend in NYC, with LA and other cities to follow.

If you tell me that art in general doesn’t have anything to do with what goes on in the world, I’ll walk away from the conversation. You and me, we got nothing to say to each other! In my writing and throughout my professional life I’ve tried to encourage cinema with a conscience and anything with the power to change the world, build bridges and create a better experience for everyone. I do also believe, deeply, that what we watch, view, read or hear changes us. And not always for the better.

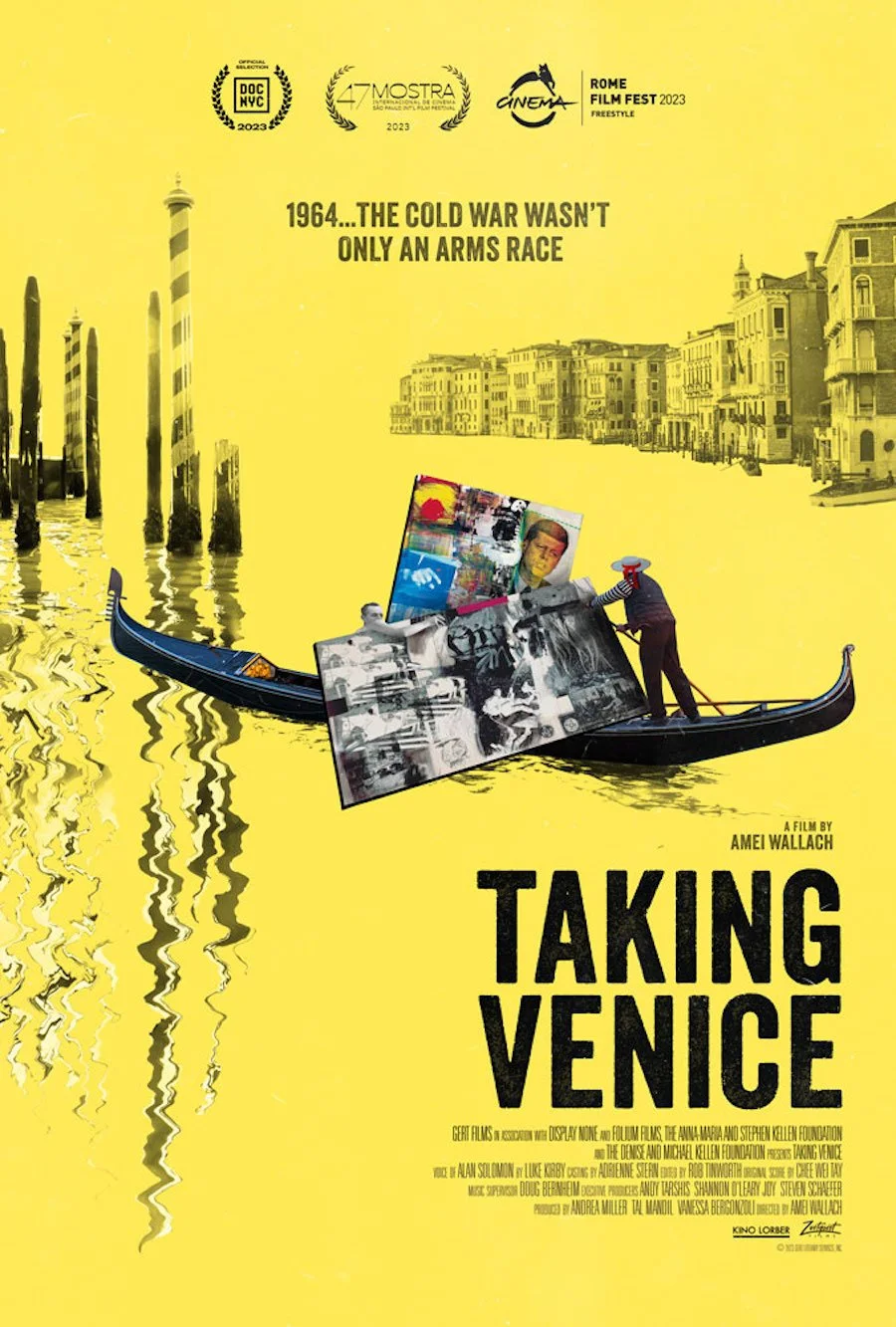

So, when I was offered the chance to view Taking Venice — a film by art critic and filmmaker Amei Wallach about the USIA and their effort in finding “cultural weapons” in order to upgrade the perception of the USA during the times of the Cold War — I jumped at the offer. And I wasn’t disappointed. The resulting documentary is an outstanding example of a film made with good intentions which also offers new perspectives and a spellbinding watch.

In 1964, the US wanted to win the Venice Art Biennale — “the Olympics of Art” as it is known, where nations compete against nations with pavilions designed and curated by esteemed members of the art world, each featuring the nation’s artists. This was a project in the midst of a year that was marked by Congress passing Public Law 88-352 (78 Stat. 241) The Civil Rights Act of 1964 which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. But it was also the year three Civil Rights workers were murdered in Mississippi and just months had passed since US President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas.

The United States Information Agency, or USIA for short, then a United States government agency devoted to the practice of public diplomacy which operated from 1953 to 1999, worked with diplomats and art dealers to bring an up and coming artist, Robert Rauschenberg, to the Venice Biennale. With his socially conscious work, which was also controversial enough to create a stir, Rauschenberg’s multi-medium paintings and sculptures would help art and politics overlap. This was to be a way out of the cultural Cold War which the US was experiencing, and no one better than Rauschenberg could embody that American renaissance movement.

Gay and hailing from a multi-cultural background, Rauschenberg represented the American dream. He had come up with a technique all his own, which incorporated silkscreened images with objects he found on the street and various materials, to create masterpieces which nowadays hail upwards of $64 millions at auction. Along with Jasper Johns, also his lover for several years, Frank Stella and a few other artists, Rauschenberg helped create a new epicenter for world art — New York City. Stealing the thunder from Paris, which up until the mid-60’s had been at the helm of the art market. Of course, this came with media cries of “junk art” and sour comments from older artists who didn’t consider him and his generation “serious artists,” whatever that means.

As the daughter of an artist myself, I know all about the issues faced by someone whose work is ahead of their times. But thankfully for Rauschenberg, Alice Denney and Leo Castelli were on his side. The former, the wife of a man who worked for the US State Department and the latter the legendary NYC Jewish Italian art dealer, helped in making Rauschenberg a name we cannot ever forget. They put him at the center of the 1964 Biennale and the rest, as they say, is history.

Denney, along with Alan Solomon — at one time the Director of The Jewish Museum in New York — created a stir in Venice. Their efforts were called anything from “Treason in Venice!” to a “Carnival” as the duo served as Vice Commissioner and Commissioner of the US Pavilion respectively. But those same efforts guaranteed that Rauschenberg became a winner. And changed the art world in one swift swoop. Or rather, a whole lot of moves that culminated in his artwork being shipped from one building to another in Venice, on a barge.

I’m sure you’ve figured by now that Wallach’s film really conquered my heart. And it is sure to get into yours too, as it proves a document to the great American potential, something we seem to have lost sight of lately. Taking Venice also reaffirms Rauschenberg as a voice of reason, someone who believed that art came with a social responsibility.

In the years following his legendary Biennale win — spoiler alert! — the artist went on to found a movement called ROCI (named after his pet turtle no less) which he used to travel the world, offering a form of cultural bridge building. Rauschenberg believed wholeheartedly in the power of art to change the world, but also how it allows people of different cultures to connect. And for that, he was called anything from a visionary and a pioneer, to a “colonizer” which of course is the easiest way to put down someone who tries to reach across borders and unite.

They always criticize the peacemakers. They are the easiest targets.

Produced by Andrea Miller, Tal Mandil and Vanessa Bergonzoli, Taking Venice is edited by Rob Tinworth — who gets a huge kudos because the film is a seamless watch! It features, among the people interviewed, Rauschenberg and Denney of course, along with archival footage of Solomon and Castelli. But also artists Christo, Shirin Neshat, Mark Bradford and Simone Leigh, the latter represented the US at the Venice Biennale in 2022.

Taking Venice opens on May 17th in NYC and May 24th in LA.

Top image and poster courtesy of Zeitgeist Films, used with permission.