The film, which world premiered at this year’s Berlinale, will enjoy its UK Premiere as part of the 3rd bi-annual Cinecittà Italian Doc Season, on July 20-21 at London’s Bertha DocHouse.

Three vital new Italian documentaries will enjoy their UK premiere at

the Bertha DocHouse this weekend, during their bi-annual film season, which this year forms part of the 100-year anniversary of the Istituto Luce.

The three films include Food for Profit by Pablo D’Ambrosi and Giulia Innocenzi and Fragments of a Life Loved by Chloé Barreau.

Near and dear to my heart is the last doc of this collection, a film titled The Secret Drawer by Costanza Quatriglio.

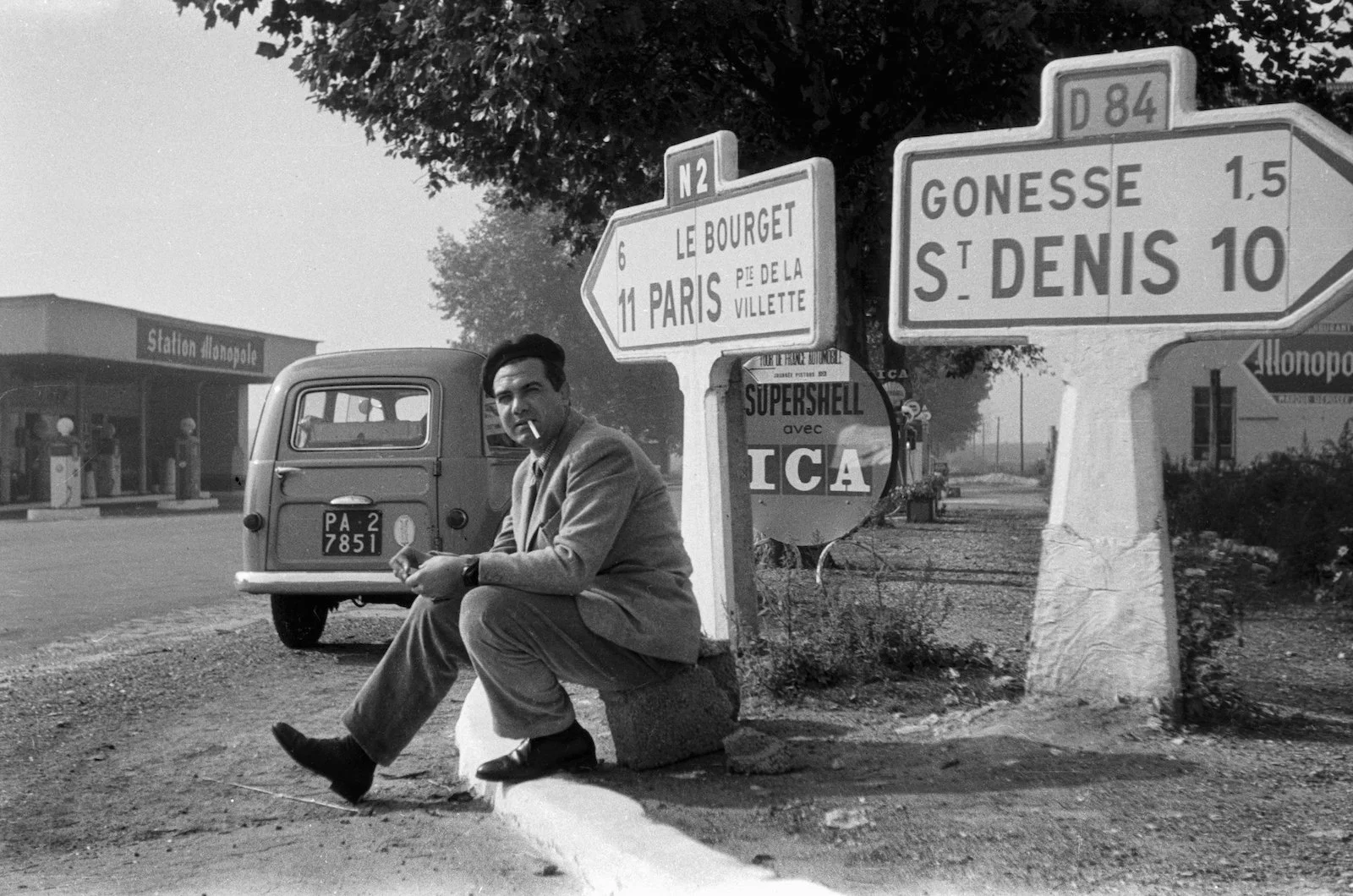

I got to watch this personal documentary, a daughter’s portrait of her historic father, at this year’s Berlinale and reviewed it for ICSfilm.org, where I gave it four and a half stars. As Quatriglio portrays cinematically her famous father, Sicilian journalist and writer Giuseppe Quatriglio, I couldn’t help but wander, in my review: “Many of us wish we could have made a film about our own illustrious relatives — if we are lucky enough to have been born into a family with one or two. But Quatriglio actually made that film we usually only dream about, beginning to immortalize her father in his bathrobe, with a handheld camera, as he talked her through his extensive archives housed in two large studies of the family’s ground floor apartment in Palermo.”

Thanks to the film’s fantastic publicist, I also got to catch up with Costanza Quatriglio, whose work includes festival favorites The Island and Terramatta. Here is the interview and don’t forget to get tickets for the screening in London this weekend by visiting the Dochouse website.

All of us would love to pay homage to the special people in our lives, but you’ve had the courage to do it, cinematically. When and how was the bud of this idea born?

Costanza Quatriglio, photo by © Azzurra Primavera

Costanza Quatriglio: The idea was born when I found, inside my house, the archivists and librarians working. They were opening and cataloguing the various books to archive. I felt that it was a very interesting feeling to describe and so I began to film it. I didn’t believe, at the start of it, that it would fit with the material I’d filmed with my father in 2010.

When I filmed him in 2010, I’d done it to keep it, and him, for myself. Only last year, while I filmed in my house and while the film took its shape, did I understand that the filming I did in 2010 was very important. That’s when I built this dialogue between absence and presence and only then did I understand I could make this film.

The film came out gradually, out of those months filming inside my house, so there isn’t a spark moment when I decided I would make it, but bit by bit, every day, this film almost made itself. While I made it, I wasn’t sure that I was making a film…

So it was more of a personal thing, to keep it for yourself… It’s interesting because while watching it, we think, as audience members, that the film was born back in 2010 when you started to film your father. It feels linear but instead, its journey was more of two parallel tracks for you?

Quatriglio: Yes, absolutely. One thing I can say, that in 2010 when I filmed my father, I remember that I was conscious of building a memory of him that, from a visual point of view, already seemed like a memory. The images that I captured then already had the flavor of an archive.

But perhaps not of a film…

Quatriglio: Not of a film! Definitely. It all came about like that..

A lot of films have been made from archival images but what is beautiful in this film is the presence of “soul”. Your soul and your father’s soul — your father’s is present in the first part, while yours is throughout the second half of the film. This special person that you are come through, which makes the film so spellbinding, so fascinating for me. The presence of these two creative spirits. Were you conscious of this “Act 1” and “Act 2” when you were building the film?

Quatriglio: When I constructed the narrative, which was while I shot, I thought that I needed to transition and I needed to change — within the film. My own position needed to change, because I felt the necessity to create a distance from my own self and to tell my own story as if I was another object, a book, a painting in the house. I am a part of that story, I’m a part of that interior, I’m part of that house so I too needed to be filmed.

But then life is much richer than a staged sequence, which is what I was doing with my DoP, and it’s therefore an impossibility — filming life.

I also believe that, beyond all, this film is also an homage to the great documentary genre, to the power of documentary, what it can be. It must surprise you, documentary cinema, so by putting my own body in the story, I proved the impossibility of faking it.

This is the era of the hybrid documentary, of reinventing documentaries that move beyond talking heads and archival footage. So what type of an audience did you imagine would watch your film?

Quatriglio: That’s a good question. I hope this film will appeal to people of different generations, and like all things that touch people’s lives, each person will be able to see something of themselves. Men of a certain age, who have asked themselves “what will be of me after?” and their children too. I think each person can find something in the film that resonates with them. This film talks to everyone, depending on which life moment they are passing through, in their lives.

I also hope this film will interest curious people, those who love humanity and who listen without prejudice.

One of the main themes, for me personally, is the idea of free journalism, which was the kind of journalism practiced during your father’s lifetime. Reporters would follow individual stories and that was celebrated and published — which isn’t done anymore. We report by press release these days. Even here, at a festival, we are forced to concentrate on Competition titles, losing out on great cinema in the process. Were you aware of this motif while making the film?

Quatriglio: I was aware of the fact that I was portraying a way of being active in the 1900’s which no longer exists. I was telling the story of a man who was very young following WWII and possessed the vitality, along with his intellectual peers of the time, to build a better world. To rebuild the world and look to the future.

I was aware that I was portraying a type of journalism which lives at the crossroads of those who write and look at the world — and the world.

All images courtesy of the filmmaker, used with permission.