“If you ask me what I came into this life to do, I will tell you: I came to live out loud.” — Émile Zola

I watch films to understand the world. And it seems sometimes the biggest lessons are just behind the scenes.

What I’ve learned so far at this year’s Venice Film Festival is that it seems if you’re a woman journalist, you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t. I’ve run the gamut from enemy of the people for publishing an interview with a man accused but never convicted of bad things, to being made to feel (by my women editors) that I don’t know how to write just so they can justify only having male writers in their roster. I also felt that a current article was unjust to the amount of women filmmakers that are actually in Venice — if the journalists who wrote it actually bothered to look at all the films, and not only the few titles in Competition — so I pointed out in another piece about a Critics’ Week title that the filmmaker was indeed a woman. And a man, I swear I can’t make this stuff up, added a comment to the FB post saying I made it sound like women filmmakers were creatures from another planet. I used the phrase “woman filmmaker” one time in the entire piece, to claim her as one of my own who makes me proud… But anyway.

That said, I still believe that cinema would be much, much different if women were allowed to write more about it and in major publications. We view films in a different way and a little care with our entertainment isn’t such a bad thing after all.

This “50/50 by 2020” movement will never be a reality of women filmmakers being picked for their talent rather than for their gender if more women film writers aren’t given a chance. Yes, there was parity in accreditation numbers in Venice this year, but how many women writers were actually published, and better yet, read?

I also believe that I’m all woman when I see further ahead and can discover great artists and hidden gems in a much clearer way.

Exhibit A below. Mark. My. Words.

‘Giants Being Lonely’ by Grear Patterson

So one such gem, a film that only a year from now male editors will be falling all over themselves to feature in their publication, is ‘Giants Being Lonely’. I’ll admit I got to watch it thanks to the relentless work of one publicist, her — yes, she’s a woman too! — insistence that I attend the official screening and then sit down with the film’s director and producer. Granted, when I saw Olmo Schnabel’s name as the latter, I was intrigued, but I gave myself more outs than even I could justify. Down to when I was standing in line for it, my personal space invaded by one obnoxious monster of an Italian queueing, and I use the term loosely, behind me, trying to push her way ahead of me. It made me want to skip the long line until I saw Schnabel’s father walk right past me, wearing a black bomber with a face painted on the back. If I had to choose one filmmaker who has explained life to me more than any other, I’d have to say it’s Julian Schnabel and knowing his son was a producer on ‘Giants Being Lonely’ made it worth the watch. Annoying pushy Italian line jumpers and all.

The best way to describe my enthusiasm for Grear Patterson’s ‘Giants Being Lonely’ is that it decodes Generation Z in a dramatic, perfectly shot and wonderfully acted way. I read recently that Millennials feel a deep sense of desperation and hopelessness for the world they’ve inherited from us, the older generations. And Patterson does show where, in an extreme situation and pushed to the limit, that desperation can lead.

He is helped by an incredible cast, which includes Jack Irving and Ben Irving, brothers in real life, as well as Lily Gavin. All fresh faces which will become the stars of tomorrow, you can be sure, just as Patterson is a filmmaker to watch. At the controls, Olmo Schnabel is the perfect producer, and during our ensemble talk together — the most delightful afternoon I spent in Venice — he directed the conversation and made sure all my questions were answered in full. The film screened in Orizzonti.

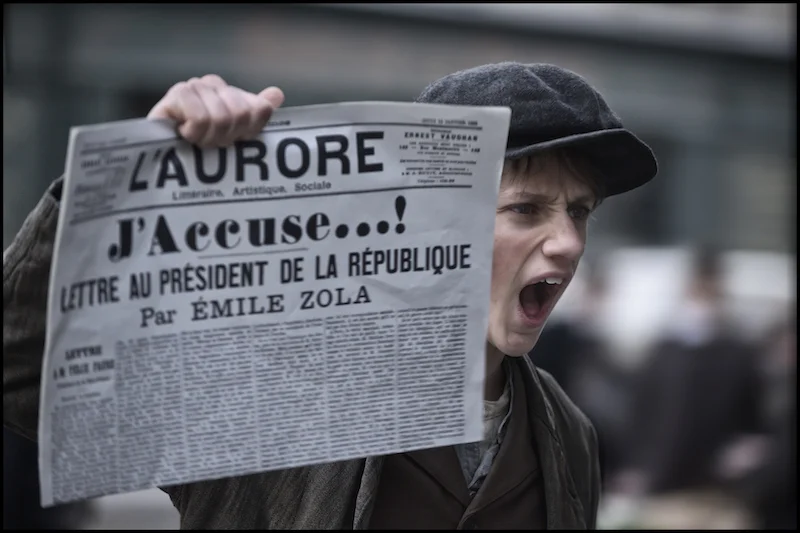

‘J’Accuse’ by Roman Polanski

“What will we ever do when there is no more Polanski?” I kept thinking as I was entertained and educated by the filmmaker’s latest.

It is fascinating to watch the great divide between the Italian critics and the English-language media when it comes to Roman Polanski’s latest masterpiece. The Italian critics’ grid place the film at the top in Venice while American and UK publications fall all over themselves trying to put it down. “If “An Officer and a Spy” flops, Roman Polanski’s reputation may not be to blame” declared one unfortunate headline. ‘An Officer and a Spy’ is the English title for the film, but i feel ‘J’Accuse’ is much more to the point.

I’ll admit I have little patience for the constant “cancel culture” cries of the #MeToo movement, particularly when it involves things that happened beyond the legal statute of limitations — yes there are laws defining that for a reason — or have been resolved already in a court of law, or through the public courts of mediation. Polanski to me needs to be henceforth judged simply on his own merit. And if we do that, watch the film without noticing he is the director (which of course he made sure we couldn’t do since he placed himself in a cameo role at one unmissable point!) we will find it a magnificent work of art which could explain the journey of every person who has ever been wronged. Is the story autobiographical for Polanski? Of course! And while Émile Zola’s front page open letter to his country is the starting point for the story, there are so many references to persecution and corruption that anyone who was ever accused of something he or she didn’t do will feel the little hairs on their arms stand up on end.

Oh, and of course Jean Dujardin and Louis Garrel are simply phenomenal. One word of advice: when the credits begin rolling, stay in your seat, as the best lines of the film are in that special little scene at the end between these two exceptional actors. Polanski’s film screened in the main Competition.

‘Scales’ by Shahad Ameen

Sitting in what is usually the conference room at the Venice Film Festival, in the dark, with a few people I’ve known most of my working life, watching Shahad Ameen’s groundbreaking ‘Scales’ I felt I was in a dream. My best, most beautifully vibrant dream where Arab mermaids exist and end up saving the world.

I’ve known Shahad Ameen since her award-winning short ‘Eye & Mermaid’ screening at the Dubai International Film Festival. That film also dealt with the theme of female empowerment and creatures coming from the sea but was completely different in tone, story and filming technique from ‘Scales’. I love both films, in their own way. And mostly because Ameen talks to my womanhood in a voice I’ve never heard before.

Shot in Oman in stunning black & white, starring Ameen’s alter ego Basima Hajjar who has been in every one of her films, and the beloved Palestinian actor Ashraf Barhoum, ‘Scales’ takes place in a dystopian, not so far away future, where a group of human beings believe that sacrificing their daughters to the ocean and later harvesting them as mermaids to feed the village is the way to go. But Hayat’s father is one of those enlightened men who won’t let that happen and so Hayat grows up — treated as a second class citizen just like the other women in her community. Until one day, when she proves herself and becomes “one of the boys,” thus changing her destiny and that of those around her forever.

Well, if you think the film has more than a subtle nod to women’s rights and our rightful place within world power, you’re absolutely right. The film, although knowing Ameen was not created with that intention, has become a political and social manifesto for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Yes, because Shahad Ameen is a modern Saudi woman and that’s probably the most stunning part of her persona. She redefines more than anyone from her country and even anyone belonging to our gender, what being a real modern woman truly is.

‘Scales’ screened in Critics’ Week in Venice.