I’ve long been a fan of everything that the Doha Film Institute has to offer. Their Qumra event is a phenomenal way to witness how filmmakers go about constructing their films, from pre-production to grants and securing funding to finish their projects. For a culture journalist, it’s a valuable way to experience, quite literally, how cinema is made.

But personally, the event that remains near and dear to my heart is always the Ajyal Film Festival. “Ajyal” in Arabic means “generations” and the film festival organized by DFI aims to inform and connect youths from different walks of life, countries, cultures and, you guessed it, generations based solely on their common interest in cinema. With a set of juries that come in all shapes, languages and sizes, Ajyal is where future film goers and film makers are formed. Both equally important to ensure a continued success for the movie industry worldwide.

This year, the festival has adapted to our current Covid-19 world and gone hybrid. For most of its international audiences and press worldwide, it is an online affair as Qatar still won’t allow tourists to enter and those living or working there need to quarantine upon returning from other countries. But for local audiences, which include all expatriates from as far around the world as you can think of, the festival offers in person, real life cinema screenings — with social distancing rules strictly enforced of course! — and drive-in movie nights. For local media, there is a media center for the festival and to those of us who have interviewed some of the filmmakers participating on Zoom, it appears like a distant, albeit pleasant dream.

Personally, I zeroed in on three Iranian films during this year’s Ajyal, and I’ll explain why. In the Middle East, there are two factions — those for and those against Iran. It’s now impossible to view Iranian cinema mostly anywhere in the Arab world and the only country taking a stance against such nonsense is Qatar. Yes, I understand geopolitical conflicts, but we’re talking about movies here people! Culture and art should be above politics but it never is… Anyway, I won’t digress too far into this, it’s a boring line of thought and the films I’m about to discuss are much more fascinating.

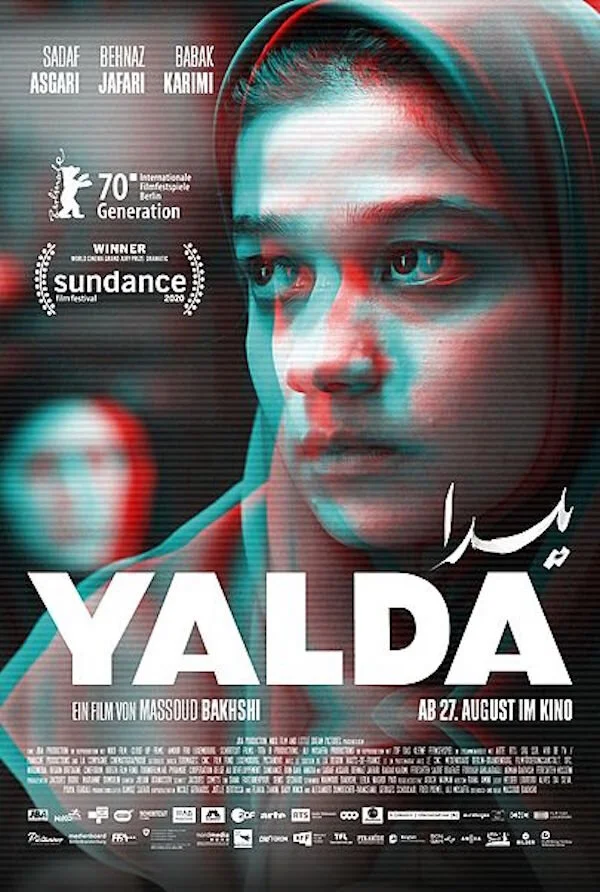

‘Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness’ by Massoud Bakhshi

When Massoud Bakhshi walked away with the World Cinema Dramatic Competition Grand Jury Prize for his second narrative feature ‘Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness’ at Sundance, I exulted. It’s not often that a film truly gets the female experience and while the film takes place in a reality TV studio in Tehran, it really could have taken place anywhere in the world. When I caught up with the filmmaker in Tehran during a press Zoom conference call yesterday, I was reminded of his great insight. At one point, he declared that in his film, “all the women are victims.” And most of the box office from a short theatrical run in Iran before the Covid-19 outbreak have been donated to incarcerated women. Can’t get cooler than that!

But what is wonderful about ‘Yalda’ — and I urge you to read the previous piece I’ve written about the film by clicking on the underlined text above — is that in Bakhshi’s work victims come in all shapes, ages and from all social backgrounds. Gone are the stereotypes that only a younger, poorer woman is a victim in today’s society. In this case even Mona, the elegant, cosmopolitan daughter of the man Maryam accidentally murdered, becomes the kind of victim that strong women can identify with. What has happened might not destroy her, or damage her in the same manner experienced by the much younger Maryam. But it will hurt her just the same, and has changed her for the worse.

My only wish is that this film had been this year’s Iranian choice to represent the country in the Best International Feature Film Oscar race.

‘180º Rule’ by Farnoosh Samadi

There is a eerie feeling that envelops the viewer as soon as Faroosh Samadi’s film ‘180º Rule’ begins. Those kitchen burners and the milk overflowing offer the cinematic equivalent of a premonition. But then Samadi skillfully takes us on a rollercoaster ride, one that the audience won’t soon forget. What appears to be a typical Iranian family, composed of Sara, the mother, Hamed, the dad and their little one Raha, will soon be turned upside down by something so tragic, so dark that days after viewing the film, I’m still dreaming about it.

I’ve since read a few reviews from when the film premiered at TIFF earlier this year and can’t wrap my head around the way film journalists think. One woman reviewer for a major trade talked about not being able to understand how a woman can change so much from the beginning to the end of the film. To those who have watched the film, and perhaps also happen to be parents themselves, I say “Hello!” Tragedy will do that to a person. To those who have yet to view the film, make sure you approach it with an open heart and it will all make sense. It made perfect sense to me.

This is another work I’d have personally chosen to represent Iran in the Oscar race, but being that the filmmaker is a woman albeit it one who is an esteemed screenwriter too, perhaps I would be aiming too high, in a society like “contemporary” Iran where the husband still has the final word on whether his wife can go out of town, to attend a wedding with her parents and family.

The title of the film refers to a rule in filmmaking which I found quite interesting. Though for me, it’s about doing a “180 degrees” as we say in the U.S. — meaning completely changing one’s direction and POV in life.

‘Sun Children’ by Majid Majidi

Finally, the actual Iranian entry in the Best International Feature Film Oscar race. I’ll start off with a statement, or simply a name. And that is — Majid Majidi! I mean, it’s Majidi and if nothing else, he’s a king in Iranian cinema.

That said, the film is a curious, well constructed look into the world of underage labor. And along the way, Majidi also introduces us to little known societal glitches like the Afghan refugee crisis in a country that already has so much to worry about internally and from its neighbors and the value of life in a place where riches are few and maintained by even fewer. Homeless, underprivileged children are a commodity and everyone around them benefits from their existence. Majidi makes that point quite convincingly. And it’s a sad statement on our world.

On the downside, ‘Sun Children’ is a collage of all the great Iranian cinema that has come before it. How is that a downside, you’re probably thinking? Well, it’s repetitive and if you’ve watched past Majidi masterpieces, along with works by the likes of Jafar Panahi, Dariush Mehrjui and Bahman Ghobadi you will recognize sequences, scenes and moments that appear repetitive in this film. But on the upside, this is a master filmmaker’s work and as such, even if you refuse certain images as I did, the whole picture does find a place deeply nestled in one’s heart and, after a couple of days, refuses to leave — I can vouch for this personally.

Even seeing the header image above, as I was constructing this piece, made me breathless.

The Ajyal Film Festival in ongoing at the moment and for your own online experience, do check out their platform here.